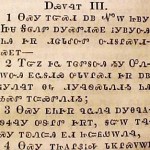

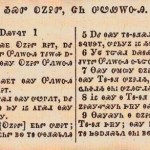

Minoritized languages moodboard: Cherokee

Cherokee (ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ Tsalagi Gawonihisdi) is an Iroquoian language spoken by the Native American Cherokee people. It is written in a unique syllabary writing system.

I replaced the incorrect picture.

Please reblog this version!

Category: Uncategorized

-

It’s #fourgodsfriday! This week, I decided to do a short mythology lesson. To the left you have Chonglin, one of the four gods of the series. Chonglin is a Qilin (pronounced chee-lin), one of the sacred mythical beasts of Chinese myth and culture. Since a lot of my readers aren’t familiar with Chinese customs, you’re probably asking, “What’s a Qilin?”

Dragons, phoenixes, and gods are familiar to most readers, so I’m going to tell you a little about this creature and why it’s one of my favorites. On the right is a picture I took about 3 years ago in a Hakka village around Tai Mo Shan in Hong Kong. My university department went for a study on historical preservation, and to welcome us, the people did a Qilin dance as a sign of respect and good fortune. Although the Qilin is revered throughout China, its dance is most common among the Hakka people and other southern Chinese cultures. The Qilin is sometimes called a unicorn, but it really isn’t since it usually has two or more horns/antlers, and is more like a dragon-deer-horse than a real horse. It appears before the birth and death of a great ruler and is a seeker of justice. In transitional times, the Qilin comes to earth and punishes the wicked and unjust usually by setting them on fire. Despite this terrifying ability, Qilin are benevolent creatures that wish no harm to come to any living being, and will only punish those who are evil. Its dance and its image are used to drive away demons and bad omens and beckon good fortune.

In #thefourgods Chonglin’s abilities to exorcise darkness and change the destiny of the empire are mentioned frequently. He is the god who helped Gen ascend and acts as his teacher most of the time, as Gen was a wise prince before he became a god. In the original Si Ling mythology, the Qilin was replaced by the white tiger to better suit the imagery. Many Qilin possess stripes, but you’ll notice Chonglin favors tiger stripes. The reason why will be revealed in Book 2. 😉 #qilin #chinesemythology #characterdesign #writerslife

-

It’s #fourgodsfriday! This week, I decided to do a short mythology lesson. To the left you have Chonglin, one of the four gods of the series. Chonglin is a Qilin (pronounced chee-lin), one of the sacred mythical beasts of Chinese myth and culture. Since a lot of my readers aren’t familiar with Chinese customs, you’re probably asking, “What’s a Qilin?”

Dragons, phoenixes, and gods are familiar to most readers, so I’m going to tell you a little about this creature and why it’s one of my favorites. On the right is a picture I took about 3 years ago in a Hakka village around Tai Mo Shan in Hong Kong. My university department went for a study on historical preservation, and to welcome us, the people did a Qilin dance as a sign of respect and good fortune. Although the Qilin is revered throughout China, its dance is most common among the Hakka people and other southern Chinese cultures. The Qilin is sometimes called a unicorn, but it really isn’t since it usually has two or more horns/antlers, and is more like a dragon-deer-horse than a real horse. It appears before the birth and death of a great ruler and is a seeker of justice. In transitional times, the Qilin comes to earth and punishes the wicked and unjust usually by setting them on fire. Despite this terrifying ability, Qilin are benevolent creatures that wish no harm to come to any living being, and will only punish those who are evil. Its dance and its image are used to drive away demons and bad omens and beckon good fortune.

In #thefourgods Chonglin’s abilities to exorcise darkness and change the destiny of the empire are mentioned frequently. He is the god who helped Gen ascend and acts as his teacher most of the time, as Gen was a wise prince before he became a god. In the original Si Ling mythology, the Qilin was replaced by the white tiger to better suit the imagery. Many Qilin possess stripes, but you’ll notice Chonglin favors tiger stripes. The reason why will be revealed in Book 2. 😉 #qilin #chinesemythology #characterdesign #writerslife

-

After putting my writing on hold for several weeks, I decided to jump back in. I expected to find all sorts of problems with my story–inconsistencies in the plot, lack of transitions, poor characterization–the works. But what began to stick out to me was something to which I’d given little thought in writing.

Filter words.

What are Filter Words?

Actually, I didn’t even know these insidious creatures had a name until I started combing the internet for info.

Filter words are those that unnecessarily filter the reader’s experience through a character’s point of view. Dark Angel’s Blog says:

“Filtering” is when you place a character between the detail you want to present and the reader. The term was started by Janet Burroway in her book On Writing.

In terms of example, you should watch out for:

- To see

- To hear

- To think

- To touch

- To wonder

- To realize

- To watch

- To look

- To seem

- To feel (or feel like)

- Can

- To decide

- To sound (or sound like)

- To know

I’m being honest when I say my manuscript is filled with these words, and the majority of them need to be edited out.

What do Filter Words Look Like?

Let’s imagine a character in your novel is walking down a street during peak hour.

You might, for example, write:

Sarah felt a sinking feeling as she realized she’d forgotten her purse back at the cafe across the street. She saw cars filing past, their bumpers end-to-end. She heard the impatient honk of horns and wondered how she could quickly cross the busy road before someone took off with her bag. But the traffic seemed impenetrable, and she decided to run to the intersection at the end of the block.

Eliminating the bolded words removes the filters that distances us, the readers, from this character’s experience:

Sarah’s stomach sank. Her purse—she’d forgotten it back at the cafe across the street. Cars filed past, their bumpers end-to-end. Horns honked impatiently. Could she make it across the road before someone took off with her bag? She ran past the impenetrable stream of traffic, toward the intersection at the end of the block.

Are Filter Words Ever Acceptable?

Of course, there are usually exceptions to every rule.

Just because filter words tend to be weak doesn’t mean they never have a place in our writing. Sometimes they are helpful and even necessary.

Susan Dennard of Let The Words Flow writes that we should use filter words when they are critical to the meaning of the sentence.

If there’s no better way to phrase something than to use a filter word, then it’s probably okay to do so.

Want to know more?

Read these other helpful articles on filter words and more great writing tips:

-

For this week’s #FourGodsFridays, I wanted to do a simple map the quadrants of China that the Four Gods rule over. Please note that this is using a modern map of China and not the correct borders of the historical Han or Three Kingdoms. The gold are Chonglin’s territories, the black are Gen’s, the light blue are Longwei’s, and the red are Fengge’s. Also note that Fengge has reign over the islands of the South China sea as well. Some of the territories are shared through overlap, and their directions also correlate to which constellations and celestial bodies they control.

In Book 1, Gen mentions having expeditions in the Ordos among nomadic tribes there, which runs through the present-day provinces of Shaanxi, Ninxia, and Inner Mongolia. These were the most northern borders of China at the time the story takes place. Chonglin’s borders would have overlapped more with Fengge’s as China’s most western border during this period would be Sichuan and up to western Xinjiang. Longwei’s territories would have extended east into what is now North Korea, and Fengge’s would go even further south into what is now Vietnam.

-

Hey all! I’ve just gotten back from Gen Con and there were TONS of writing seminars there, one being how to write alternative history. Historical fiction, sci-fi, and fantasy have become so intertwined lately and a lot of writers are delving into the genre to start meshing more popular genres with historical backdrops. Seeing as how The Four Gods is a historical fantasy and alternative history and how relevant those panels were, I thought a review on some basics of historical fiction writing would be in order.

1. Pick Your Poison

First and foremost, choose your time period and area of historical fiction you will be writing in. Don’t you know, historical fiction has multiple sub-categories like all genres! Are you writing traditional historical fiction that only encompasses an event that could have happened in a given time period? Are you writing speculative fiction that involves fantasy, sci-fi, and a lot of what-ifs with famous events? Whatever you choose, pick your time period, get an idea of your characters, and get your time machine ready.

2. Research

Research is key to demonstrating sufficient knowledge of the period you have chosen to write about. Look into books, articles, and if you can, interviews– or as I like to call it, “hands-on history.” You also have to know how to research. Wikipedia is a good springboard, but should never be used by itself. Look into the source list of the article you’re reading, or if you pick up books or physical articles from academic sources, look at their sources. Of course, it is up to each author to how much research is necessary, which depends on how deep your manuscript goes into the time period you have chosen.

If you are still in college and have access to online libraries, use them! JSTOR and EBSCOHost were invaluable research tools that I had at my disposal since I began writing The Moon-Eyed Ones when I was still in my Master’s program.

As for my “hands-on history” approach, museums and primary sources are wonderful tools. For instance, The Moon-Eyed Ones takes place in 1835-38 Tennessee, which was based on the area my family lives in. I used the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina and Conner Prairie Interactive History Park here in Indianapolis as two of my big resources, as the Cherokee Museum has artifacts and tidbits I had missed, and Conner Prairie as an interactive setting let me use all of my senses and completely immerse myself into what it may have been like to live in the mid 1830s (and have a little fun on top of that :P).

Note: Also be prepared, depending on your subject matter, to run across sources in multiple languages.

3. Character Construction and World Building

Characters are the lifeblood of a story, and when writing historical fiction, you may have more restrictions than if you were writing in another genre. Your characters must conform to the time period you have chosen. For example, Silas in The Moon-Eyed Ones is affected by laws at the time that forbid him from voting or having a voice in public hearings. Because of his race (or perceived race), he is forbidden from certain activities that he would have no problems doing if he lived today. Be careful to not include references or abilities to modern privileges or luxuries. If you are writing speculative fiction, then you have a little more free space to run around and mess up the space-time continuum or include inaccuracies.

Same goes for your setting. What do houses or buildings look like? Did your character have access to electricity, running water, or transportation other than their own two feet? How accessible were stores, towns, or other gathering places? What occupations were available? How does your character eat, dress, or bathe, and how often? Keep an eye on modern amenities trying to sneak their way into your manuscript, as you may be shocked to find out that your dashing male lead may have only bathed once every week or two.

4. Say what?!

Language is important when your characters are speaking, especially if your story takes place many centuries in the past. I myself find this one of the most challenging aspects of writing historical fiction because while I would like everything to be accurate as possible, I would also like my story to be readable. For example, back in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Melungeons have been noted by some sources to have spoken a hodgepodge of Elizabethan English and the American English we know today. The language patterns are still apparent in many dialects of the Southern American accent, but how far is too far? Tread lightly here, and pepper in what you can, but use beta reviews and other reader opinions to gauge if your characters sound too modern or if they can’t be understood at all.

Another note on this is that depending on your time period, the people in your story may have a few things to say about certain things that would seem racist, offensive, and downright horrifying to our modern sensibilities. The “How far is too far?” question arises here more than ever, and while I personally don’t like sacrificing historical accuracy to make everyone sing Kumbaya, it all depends on your manuscript. But in this regard especially, should you run into this problem, be prepared to make your readers uncomfortable.

5. Read!

Yes, read! I personally like reading books with similar subject matter and in similar settings when I am writing, but reading, in general, is a given (especially because you’ll be researching). When I was writing the first draft of The Moon-Eyed Ones, I went for any fiction that involved Melungeons, Cherokees, or the American South in the 19th and early 20th C. To be honest, I didn’t enjoy every single book I picked up, but reading gave me insight on what I enjoyed, how the writing was executed in regards to the points above, or even what not to do. Reading makes you a better writer and can give you a better idea of what you want your manuscript to accomplish.

—-

And there you have it, the top 5 aspects of getting that historical fiction novel written! Of course, these are true with any piece of fiction and keeping your writing on track.

-

-